Against Butterflies

By Ann Lauinger

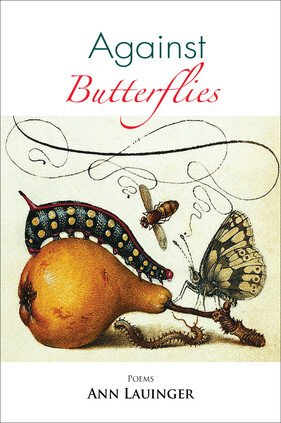

($19.95, (7” X 10”) Paperback, 132 pages – including 26 full-color illustrations by Joris Hoefnagel from the Calligraphiae Monumenta)

Winner of the Vernice Quebodeaux “Pathways” Poetry Prize

INTRODUCTION

Its title notwithstanding, this book isn’t against butterflies, or even about them. Who could seriously be against those beautiful, endlessly variegated, delicate, winged creatures? It might be easier to be against a mother’s love or clean air.

I should explain, then. The idea for the poem, “Against Butterflies,” which gives its title to the whole collection, began years ago with a visit to the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, where I happened to see on exhibit a print illuminated by the Renaissance artist Joris Hoefnagel (the image portion of the print is reproduced on the cover of this book). I was very struck by the piece, which seemed to me both genuinely creepy and astonishingly lovely. The book in which the print appeared, Mira Calligraphiae Monumenta (literally, Amazing Records of Calligraphy), was a deluxe edition of an instructional manual of lettering by Georg Bocskay. But, in true Renaissance fashion, the creator did not waste the opportunity for moral improvement. Instead of an alphabet or a random series of letters, the example of calligraphy presented on the page is a pious Latin prayer, which translates roughly as: God, you who know that we, for our human frailty, set among such great dangers, cannot stand: give us health and life.

I should explain, then. The idea for the poem, “Against Butterflies,” which gives its title to the whole collection, began years ago with a visit to the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, where I happened to see on exhibit a print illuminated by the Renaissance artist Joris Hoefnagel (the image portion of the print is reproduced on the cover of this book). I was very struck by the piece, which seemed to me both genuinely creepy and astonishingly lovely. The book in which the print appeared, Mira Calligraphiae Monumenta (literally, Amazing Records of Calligraphy), was a deluxe edition of an instructional manual of lettering by Georg Bocskay. But, in true Renaissance fashion, the creator did not waste the opportunity for moral improvement. Instead of an alphabet or a random series of letters, the example of calligraphy presented on the page is a pious Latin prayer, which translates roughly as: God, you who know that we, for our human frailty, set among such great dangers, cannot stand: give us health and life.

I craved that piece of art, and I was thrilled to find in the museum store a reproduction of it, which now hangs next to my front door at home. Every time I leave the house I see it, and I’ve spent more time than I like to acknowledge staring at the images and muttering over the Latin moral. So the poem I eventually wrote probably grew out of my fascination with Hoefnagel’s images and my desire to fashion in words some kind of equivalent for their beauty and their repulsiveness. In doing that, I found myself thinking about my reaction to that prayer and its relation to what’s depicted. The solitary pear, portrayed in all its sumptuousness, its appeal to our visual and gustatory delight, is clearly doomed to rot, if it isn’t wholly devoured by the predatory insects that, though smaller, outnumber it and have already made contact with its delicate skin. Frailty and impermanence, growth, metamorphosis, and decay—all these rather daunting ideas ran through my mind whenever I looked at the work; in the end, I suppose I used Hoefnagel’s print to help me think about them.

There are doubtless as many ideas of what makes a book-length collection as there are poets—and readers of poetry. According to one view, a collection ought to be tightly unified in subject and be about something specific: the 1919 Black Sox scandal, say, or the inventions of Thomas Alva Edison, or living with a painful disease. I’ve invented these examples, but they are not far-fetched, I assure you. And what their actual counterparts illustrate is one prominent strand in contemporary poetry: a taste for facts. Not just in poetry but in all forms of entertainment these days, we like to know that what we are being told is real.

But there are other ways to compose a book of poems, and coherence or unity also is born out of style and sensibility. Poems do reflect a way of seeing the world and ourselves, and, like most people, a poet generally has characteristic attitudes and preoccupations, fears and delights. Whatever a poem is nominally “about,” the things that make it a poem and not a document are also what make it characteristic of its writer: not the subject but the stance toward the subject; and, allied to that stance, the style of the piece, by which I mean not just whether it is written in free verse or metrical form but all the ways the resources of language have been marshaled to create a patterned whole for eye and ear.

So while Against Butterflies is not “about” butterflies—or any other topic, for that matter—I did discover, in the process of putting the collection together, some persistent themes and concerns. I didn’t write the poems to order for this book; on the contrary, they originated over a span of years. It was on the one hand gratifying to see connections among them because that meant the book had a reason to be a book; but on the other hand, it was slightly embarrassing to see revealed on page after page my inner life. Not, I hasten to add, the persons, places, or acts of my life: I’m no memoirist. It was more like looking at a map of my emotional terrain, and I came to recognize, in much of what I had written over these years, the essential consistency of my loves, my dreads, and many feelings in between.

Being awarded the Vernice Quebodeaux “Pathways” Poetry Prize by judge Richard Harteis and having this book published by Little Red Tree has been very gratifying. But one particular pleasure associated with the prize became apparent to me only once I began to work with the publisher, Michael Linnard. Deciding to take the manuscript’s title seriously in his design, Michael has fashioned a book I would never have been able to envision. Most obviously, in drawing illustrations from the rest of Hoefnagel’s manual, he has created a volume of great beauty. But these images also furnish the book with their own kind of unity, building on the centrality of the title poem and perhaps prompting a reader’s recognition of how many other poems in the book arise from a kind of ground-level view of the small things in nature (including, surprisingly, quite a few insects, though I’m not over-fond of that life-form!).

If you’ve followed me so far in my disclaimers as to what this book isn’t, you may be wondering how I came to write poetry at all. Although I’ve just confessed that my poetry isn’t confessional, I guess an introduction may be allowed to be so, and I’ll try to trace briefly here my path to the page. In the broadest sense, of course, every writer is confessional, since all writers write from the experience of being alive, of being themselves. But I tend to be sparing in my poems of real-life detail. Real events and real relationships underpin some of my poems, but I’m usually able to write about them only obliquely, seeing them refracted through certain images, for example. Sometimes I discover myself caught by a sequence of words—a first line for a poem—that then suggests other sequences with a kind of musical or poetic logic of its own. When I’m not thinking actively or even consciously about a given subject but am focused more narrowly on technical matters of sound and image, my feelings seem to become deeper, more intense, and yet more available to feed whatever I’m writing.

I’ve been a reader of poetry for much longer than I’ve been a writer of it; only rather recently have I come to think of myself as a poet, and it’s more recently still that I’ve managed to identify myself as one out loud. My road to writing was less through any felt need to express myself than through a deep pleasure, dating back to my childhood, in all aspects of language: words, sounds, rhythms; contemporary slang and the obsolete vocabulary and archaic phrasings of Chaucer and Shakespeare; nonsense and wordplay of all kinds. The poets I read as a student and am lucky enough to teach for a living have always given me incomparable delight; now that I’m a writer, our relationship has only grown more complex. In addition to pleasure, they offer me instruction, inspiration, and sometimes criticism that pulls no punches. In particular, I would name Vergil, the Beowulf-poet, Ben Jonson, Andrew Marvell, Pope, Keats, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Elinor Wylie, W. H. Auden, among so many more that at times it feels as though my brain is running a boarding house for poets, where the contentious lodgers gather around the dinner table for recitations and food fights. But I can’t imagine writing—or existing, for that matter—without them. How grateful I am for everything they give, and how happy I feel to be in their debt.

Ann Lauinger

Ossining, NY, March 2013

AGAINST BUTTERFLIES

Deus qui nos in tantis periculis constitutos

Deus qui nos in tantis periculis constitutos

Pro humana scis fragilitate non posse subsistere

Da nobis salutem.

Mira Calligraphiae Monumenta

(illuminated by Joris Hoefnagel, c. 1590-6, Getty Museum)

Don’t you realize that we are worms,

Born to form the angelic butterfly?

Purgatorio

Like a pregnant woman on her back,

the pear in Hoefnagel’s illumination

lies belly up, ochre

ripeness prostrate. Triumphant,

a large moth marches up the neck;

a smaller dives like a biplane.

The tapered stem’s convex

shelters a worm, hairy, thin,

and feeble as a sulking infant. Facts:

we are fallen and flesh is rotting.

The future? No heaven is painted here,

except a fat caterpillar squatting—

dark slice of the celestial, fire-

striped midnight blue, studded

with gold as if with stars—

on the silk-smooth mound,

where eight wiry suction feet

of this glutton or god

mean to grip tight.

Above, a delicate calligraphy

in place of sky entreats,

God, you who know that we,

set here, humanly frail amid

so many perils, can have no stay:

save us. In other words:

Make me a butterfly,

not compost, Lord.

* * *

That was the old world. But we

That was the old world. But we

nourish our own winged pieties,

would rather wake than sleep

and, licensed to pursue satiety,

keep falling off the carnal wagon

because we crave uplift, the diet

of Consciousness, a flabby dragon

in charge of the very choicest gardens.

All scales and smoke, zig-zagging

from pride to self-pity, snorting

indignation, he soars and creeps

and whines about the winged-thing’s burden

as if he had some genuine gripe,

when his tinsel hoard of lucubrations

isn’t a patch on a pear that’s ripe.

Worms ply an honest corruption,

wit enough. As good as a sage,

the caterpillar glorying in no translation,

simple pillager who chews into change.

Facts: a scuttling catbird

picks the brickwork for ants. Cicada-

curtains are shaken and furled.

Late brilliance of asters razzles

pithless stalks and empty pods.

We’ve done much—done marvels.

But we can have no stay, set here

without wand or chalice.

And nothing can be more sure

than that nothing requires our surviving

this mutable fête en plein air.

Regard, messieurs et dames, the removing

of the tablecloth: not the tilt of a pear

disturbed. The conjuror vanishes next, waving

the small white damasked square.