The Cancer Diaries: Book One ~ Flood Warning

By W.F. Lantry

($22.95, (7” X 10”) Paperback, 128 pages, 26 full-color images)

What happens when the wife of a prize-winning poet develops breast cancer? When her biopsy results came back, Kate Lantry sat her husband down and made a serious request. “I want you to document this cancer journey. I want you to go back to writing a poem every day. I want you to write about exactly what happens, as accurately as you can. Don’t leave anything out.”

He told her he had covid fog, and could barely think, much less write. She said, ‘If I can face all this again, you can write a few poems.’ He told her he would.

He hadn’t yet heard the phrase ‘tell your story of how you overcame everything, and it will become someone else’s survival guide.’ He didn’t know how much these poems would mean to others as he posted them on social media, day by day. Women who had gone through similar trials, spouses who loved them, family members who had lost their mothers, daughters, and wives. As time went on, new people wrote him, people who had been newly diagnosed, and who were terrified, but they said that if Kate could go through this, so could they, and her story gave them courage to face what had to be done.

And so he wrote, day by day, poem by poem. He documented their lives, their garden, their daily walks in the park, and all aspects of her treatment journey, as they entered the unfamiliar world of biopsies and ultrasounds, of Chemo and immunotherapy, of surgery and proton radiation.

Book One tells the story of April, the time of her diagnosis, through the end of June when Chemo had to be paused.

Flood Warning

A quiet evening. Dark. And rain outside—

They say we’ll get four inches before dawn.

I’m in the kitchen while she sleeps upstairs.

Another day of biopsies, x-rays,

of ultrasounds and needles for the pain:

she’s not supposed to pick up anything.

I’m cooking, listening to Keren Ann

whose voice reminds of Paris in the Spring

how many years ago in rain like this:

“The only things I still know how to make

are water ripples on the waveless Seine.”

And me? I’m making rice and eggs. Young James

Still has an appetite, and needs to eat.

Outside, the rain keeps falling, and the wind

moves through the leafless trees of early Spring.

I stand and stare at nothing, at the wind.

I cannot see into this foreign dark

where songs and shadows merge with endless rain.

INTRODUCTION

I spend my days wandering around the garden with no real plan in mind: gazing at flowers, tying up vines, uprooting the occasional weed: such is the peaceful life of a humble gardener poet. It’s a small garden, as such things go, but still, there are so many things needing attention any rational person would be overwhelmed when faced with today’s list. So I simply walk along one of the garden’s paths and try to address whatever I find. There’s a kind of freedom in unplanned action, the joy of wandering through a daze among the blossoms.

It was mid-afternoon, and I was near the lotus pond when the phone rang. It was Kate, my wife, known to her family as Kathy, known to the musical world as Kathleen Fitzpatrick. But poets and writers know her as Kate, and she is deeply loved by the community, for good reason, both here and abroad. Fifteen years ago she came to me, at the height of my professional career, and said “What are you doing? You’re wasting your life. You haven’t written anything in years. I want you to write one thing each day, a poem or a story, anything, and I’ll send them out to be published. You’re not allowed to come home for dinner until you’ve sent me something.”

The results were, to say the least, surprising. Publications, books, prizes, and awards, all due to her. When we did interviews, people didn’t ask me many questions, they were far more interested in hearing from her. When we did poetry conferences, she’d hang back for the first couple minutes, and then she’d be out there, center stage, holding forth to a rapt audience, answering every inquiry and pointing out the direction for our journal, her journal: Peacock Journal. And it’s not even her field, she’s a coloratura soprano, with a voice that could melt all your resistance, pull back the veil, and open a portal to a timeless world of beauty and grace. Everything I’ve written since we met is a tribute to her. People, famous writers, would actually raise their hands and ask “Do you have a sister? I need a clone of you!” But medical science hasn’t advanced that far, and she has no sisters: there’s only one Kate, and though she may seem like a figure from an elegant dream vision, “she is mortal, and by the grace of providence she’s mine.”

So there I was, by the lotus pond, taking a break and watching the koi moving in their endless figure eights beneath the surface, when I answered the phone and heard her voice. If you must know, I love her voice so much sometimes I just listen just to listen. I am the most fortunate of men. But this time her voice was different, and it reached through the pleasant haze of my wanderings and woke me up. I actually asked myself ‘What is she saying?’

She was saying she was at the gynecologist, and he’d found something, on the same side, and he was recommending a biopsy. Suddenly, I was completely awake. The same side? Twenty years ago, only a few weeks after we started dating, she found a lump in her breast. She had no idea how long it had been there, at the time she said she only found it because of my touch. Still just dating, we went through a whole series of medical visits, then surgery, then radiation. I tried to be there with her at every step, at every appointment. Even though we were nothing official to each other, I already loved her, as you may well have guessed, and anyway, no-one should have to go through such things alone. Five years later, I wrote this poem about those times:

Five Years

Before the discrete markings in her skin

could let well-tuned machines triangulate

the radiation beamed into her breast,

before the chemicals and all the drugs,

before the morning visit could divide

her life as previous or subsequent,

I drove her, with no rights, one afternoon

and walked her in. The nurses made me wait,

so all I have is second-hand. It seems

at first the anesthetic didn’t take.

She said, “Is it supposed to hurt?” Their eyes

in panic told her no. Another shot

and then the knife went in. The miracle

came when they asked her what she did. “I sing.”

“Sing us a song then…” As the knife explored

deep past the lymph, into her flesh, she sang

Lost Annachie, the first tune she had sung

to me, one afternoon, forgetting all

the words, which I supplied between the chords.

I was not there to give them, but she sang

what she remembered as they brought her out.

I held her then just as I hold her now

and each day, still, I notice those tattoos

between her breasts, and relish every breath.

The doctor told her at the time that while there’s no good kind of breast cancer, her’s was maybe the best kind to have. Slow growing, not terribly invasive. The surgery was successful. Nobody talks about cures when breast cancer is involved, instead, they say they can find NED, “No Evidence of Disease.” She chose post-surgical radiation over chemotherapy because, as she told her doctor, ‘I may want to have a child with the man who will be my husband soon.’ She didn’t tell me that, she only told her doctor. She always plays her cards close to her vest. Everything about her is subtle and delicate.

And so we put all that in our rearview mirror. A year later we were married, and then our son James was born. She wanted a house so we bought one, she wanted a center hall colonial. OK, and I want a garden. A real, permanent garden. I had spent many years as a university professor, I’d taught at twelve universities on two continents, and everywhere I went I made a garden, and when I moved on to the next post, every one of those gardens was turned back into lawn. But I’d left the classroom, and taken a position as Director of Academic Technology at a research university, and I had reason to hope for a garden with greater permanence. Alas, there was a housing boom, and the only house we could afford was a rundown three-story outside the beltway. It needed a lot of work. As soon as we moved in, I commandeered the garage and turned it into a wood shop so I could work on the renovations. The garden would have to wait.

It waited a long time. James started school. Both my parents passed away, one from cancer. And her mother, also from cancer. And my oldest brother. The university restructured, and I found myself in early retirement. She was still singing, to audiences of hundreds, even thousands, every weekend. It was her calling, and she loved it. Then Covid arrived.

We figured James brought it home from high school. It was February 2020. I caught it first, and it was not good. My doctor’s office refused to see me and suggested I go straight to the hospital. The hospital had no desire to see a potential Covid patient walk through the door. So I stayed in bed for ten days, sicker than I’ve ever been. Kate and James both had mild cases. I never really got better, and ended up in the hospital that summer, with what people now call long Covid. No-one was using that phrase at the time.

Having faced all that, in September I recalled my garden plans, and decided to build a greenhouse. I was still sick: many days it was all I could do to sit in the site I’d started clearing. But I was determined. In the midst of the pandemic, lumber was hard to find, all kinds of materials were hard to find. I sat out there, and some days managed to pick up a hammer, or a saw. September passed, and then October. The work seemed to strengthen me. By November, the frame was up. In December, I got it closed in.

She was Director of Music in a church. Covid closed the church. She decided she wanted to go back to teaching and started working on that. I was building the garden: raised beds, fences, gates, ponds. One pond in the greenhouse. A small pond on the slope overlooking the Anacostia river. And the big pond, the lotus pond, at the center of the garden.

That’s where I was when the phone call came. And a week later, when the biopsy results came back, she sat me down and made a serious request. “I want you to go back to writing a poem every day. I want you to document this cancer journey. I want you to write about exactly what happens, as accurately as you can. Don’t leave anything out.”

I told her I had Covid fog, and could barely think, much less write. I told her I didn’t have that kind of energy. She said ‘If I can face all this again, you can write a few poems.’ I told her I would.

I didn’t do it simply because she asked, although that would have been enough. I had lost some old friends recently, one an editor, the other a poet. It’s a strange phenomenon: people will be writing things, doing things, and posting online about them, and then imperceptibly the posts would drop off. But with so much happening it’s hard to notice the absence of things, to hear silence amid all the noise. And these two women made a choice so many do: they didn’t talk about their cancer diagnosis. They didn’t tell their friends. They stopped communicating with everyone, withdrew into themselves, and then disappeared into the silence. Most of us only found out when someone forwarded their obituaries.

I didn’t want that for Kate. She was not going to go gentle into the night, or quietly. She wasn’t going to just disappear. That was my first motivation. We all want permanence. These are my favorite lines from Ovid:

Give me yourself as matter for my song:

The songs will come back worthy of their cause.

Europa, Io, Leda live as long

As we keep reading poets with applause.

So may our legend last while verse endures

And all that time my name be linked with yours.

Later, there would be other motivations. I hadn’t yet heard the phrase ‘tell your story of how you overcame everything, and it will become someone else’s survival guide.’ I didn’t know how much these poems would mean to others as I posted them, day by day. Women who had gone through similar trials, spouses who loved them, family members who had lost their mothers, daughters, wives. As time went on, new people wrote me, people who had been newly diagnosed, and who were terrified, but they said that if Kate could go through this, so could they, and her story gave them courage to face what had to be done. But I didn’t know that then. All I knew was that she was sick. And she asked me to do something. And I promised to do it.

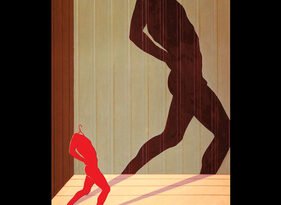

But I didn’t start right away. It was actually a few days later. I had already taken over the household duties, including the cooking. A stormy Friday evening. She was exhausted, sleeping upstairs before dinner. James was in his room. I was in the kitchen, starting dinner when I heard the flood warning on the radio. Four inches of rain predicted. I looked out the kitchen window, trying to see through the darkness whether the river was already rising. And I was overcome by a strange emotion, something I’d never felt before. So I turned off the stove, walked upstairs, and wrote the first poem. And I called it Flood Warning.

W.F. Lantry

Washington D.C. 2023