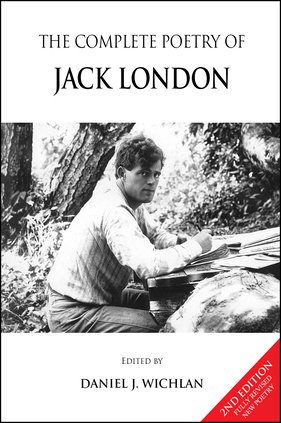

The Complete Poetry Of Jack London [2nd Edition]

By Daniel J. Wichlan

($19.95, (7” X 10”) Paperback, 266 pages, 17 b/w photographs)

![]()

[See below Professor Earle Labor’s review of the 2nd Edition]

First published in 2009, we are now pleased to release this fully revised and updated 2nd edition of The Complete Poetry of Jack London edited by Daniel J Wichlan.

The new edition contains a new introduction, new poetry and newly attributed poetry plus numerous photos of Jack and his wife’s and children.

In this groundbreaking book, the true genesis of Jack London’s prose style is at last revealed. This book will forever alter the established view and perception of one of America’s most famous writers.

Behind this modest title hides a wealth of new works previous unpublished, together with revelatory analysis, notes and information relating to all the extracts of poetry discovered in both London’s published and unpublished writing.

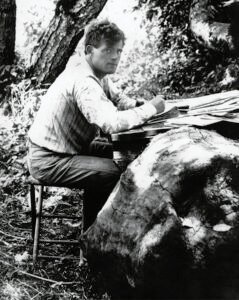

Simply put, Jack London was a poet who wrote fiction and nonfiction not a writer of fiction and nonfiction who wrote poetry. This was his declared intention at the start of his writing career. However, his poetic aspiration and passion were sublimated under the weight of the necessity to earn sufficient money to support himself and his family.

As Daniel so clearly states, in his extended introduction, “Jack London had the heart and soul of a poet as demonstrated by his love of and passion for poetry…” and that “Few prose writers exceed his knowledge and understanding of writing poetry…” and “London used poetry, his and others, extensively throughout his writing, in fact, thirty-one of his fifty-one books contain significant amounts of poetry.” All extracts are reproduced with comprehensive attribution.

Daniel goes on to say that “London owes much of his success to the richness of language and emotionally stirring descriptions used throughout his writing. This language and these descriptions frequently reached lyrical levels as in his masterpiece The Call of the Wild and its “sequel” White Fang. London’s poetic instinct is the origin of his writing prowess…”

Therefore, this book is essential reading for those interested in understanding Jack London, as never before, and discovering the central role poetry played in his life, which was crucial to the development of his lyrical style of prose writing.

A NATURAL-BORN POET

Professor Earle Labor’s Oct 2014 review of the 2nd Edition

Among members of the general reading public, as well as the academic establishment, Jack London is best known as the author of a couple of wonderful stories about dogs in the Northland. Until recently, despite London’s own clearly stated preference for writing poetry instead of fiction, even most Jack London fans and scholars were mainly familiar with his stories, novels, and political essays. Although I myself had been seriously studying London’s works for nearly a half-century, my own knowledge of his poetical talent was limited to the half-dozen or so verses he’d inserted in his fiction—most of which I regarded as little better than doggerel.

I changed my mind seven years ago when I read the remarkable collection of London’s poems capably edited by Dan Wichlan. Jack London was significantly more than a “jingle-man” (as Emerson called Edgar Allan Poe). He was, in fact, a very good poet with a fine ear for lyrics as well as a sharp eye for imagery. He also possessed a close familiarity with the works of major poets, many of whom he was fond of reading out loud. Note this partial list: Blake, Browning, Chaucer, Dante, Dryden, Goldsmith, Milton, Poe, Pope, Shakespeare, Shelley, Tennyson, Wordsworth, and many more. Had he been able to devote his extraordinary creative ability to his preferred field—i.e., if he had possessed the financial means—Jack London might have become a poet of at least minor significance in American literary history.

Unfortunately, his creative genius—like that of his idealized poetical maestro George Sterling—was bound by traditional but by the turn of the twentieth century outdated linguistic and technical strictures. Consequently, most of his poems are derivative in diction and form, while lacking technical innovation. However, this doesn’t mean that they are also lacking in thematic impact. A poem like “The Way of War,” for instance, is comparable to Stephen Crane’s celebrated war poetry, as witnessed by the following stanzas:

Future man—ah! who can say?—

May blow to smithereens our earth;

In the course of warrior play

Fling death across the heavens’ girth.

Future man may hurl the stars,

Leash the comets, o’er-ride space,

Sear the universe with scars,

In the fight ’twixt race and race.

Writing an early letter to his friend Ted Applegarth, in addition to precisely detailing the basic rules for meter and stanza, London inadvertently revealed both his major weakness as a poet and his major strength as a writer of fiction: “Poetry in the English language is bound to always be stilted, but the true aim of the artist should be, or the very essence of the art is to reduce the stilt to a minimum & still musically voice the poetic thought or fancy.” A decade later, Robert Frost would demonstrate that the English language is hardly bound to always be stilted. On the other hand, Jack would reduce stilt to a minimum and still musically voice thought in his fiction.

To Wichlan’s credit, he makes no claim for London’s reputation as a poet. In his “Preface to the Second Edition,” he states quite clearly, “The thesis of the book is that the significance of London’s poetry and his love of poetry is not the poetry itself but rather how it influenced his writing and how it energized his creativity.” In other words, poetry was the genesis of Jack London’s success as a master of the short story and novel. Demonstrating how “Prose and poetry were closely integrated in London’s mind,” Wichlan quotes lyrical passages from Chapters III and V of The Call of the Wild and the opening paragraph of White Fang. One of my own favorite passages appears in the concluding Chapter VII, which Jack’s daughter Joan considered the most beautiful her father ever wrote:

“The months came and went, and back and forth they twisted through the uncharted vastness, where no men were but where men had been if the Lost Cabin were true. They went across divides in summer blizzards, shivered under the midnight sun on naked mountains between the timberline and the eternal snows, dropped into summer valleys amid swarming gnats and flies, and in the shadows of glaciers picked strawberries and flowers as ripe and fair as any the Southland could boast. In the fall of the year, they penetrated a weird lake country, sad and silent, where wildfowl had been but where then there was no life nor sign of life—only the blowing of chill winds, the forming of ice in sheltered places, and the melancholy rippling of waves on lonely beaches.”

Buttressed by a lifetime dedication to Jack London and more than three decades of serious scholarly work, Wichlan’s impressive book comprises much more than London’s complete poetry—both published and unpublished poems (as best known by the editor’s extensive research). A treasure-trove of invaluable information, it also includes substantial sections on poems in London’s writings both attributed and unattributed to others (with specific information on sources), plays in verse attributed to London and George Sterling (under London’s name), Jack’s book inscriptions to his wives and daughters, a copy of London’s No. 1 Magazine Sales notebook detailing his prosodic studies, a chronological biography, and a list of London’s first editions. I should point out that Wichlan’s perceptive editorial comments are themselves exemplary, signalizing a valuable contribution to London scholarship.

This Revised Second Edition both supplements and complements the First Edition. In addition to the results of further research, corrections, and a new Preface, this edition is especially noteworthy with the discovery of a delightful parody of Christopher Marlowe’s famous poem “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love.” Jack’s version, inspired by Anna Strunsky in co-authoring their Kempton-Wace Letters, is titled “A Passionate Author to His Love” and concludes on a whimsical monetary note:

These tender things we’ll put in print.

Sweetheart there may be millions in’t!

The public simply can’t resist

“Love Letters of a Socialist.”

We’ll turn our passion to account,

And realize a large amount.

If the plan thou dost approve

Come write to me and be my Love.

While neither The Kempton-Wace Letters nor their passion would “realize a large amount,” Jack London’s passion for poetry transmuted into fiction would realize a bonanza.

Professor Earle Labor

Centenary College of Louisiana